|

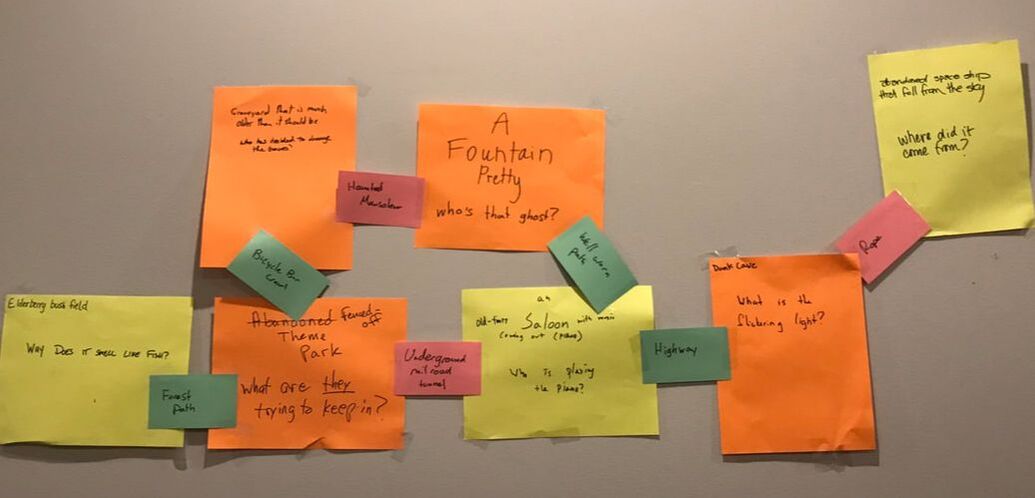

A few weeks ago my friend Mark (@echolocated) reached out asking to pick my brain about mapmaking activities for a rehearsal plan built around creating space. He had played a couple different games with me where we made maps together, and he was curious about using those approaches to create a shared world with his ensemble. I was super excited about the prompt because games and theatre both define spaces and I thought there might be some cool interactions between the two. Today we’re going to look at developing maps and shared locations and get into why this is a great tool for devised theatre work.

1 Comment

I’ve only made it out to a small tiny slice of the shows offered in the Fringe this year, but thanks to my other life as a bartender I saw four performances of Gay Mis and it might be the best show of the fesitval. Gay Mis, if it isn’t obvious, is a queer, drag queen-infused parody of Les Miserables created, produced and performed by Eric Jaffe along with a stunning cast. It’s a follow up of sorts to Thweeney Todd: The Flaming Barber of Fleek Street. Gay Mis is a colossal offering and I haven’t stopped thinking about it all week.

Let me cut right to the cheese: this show is dumb. The jokes are wonderfully stupid, and at times fabulously obvious, a line that evokes explosive applause one night brings out a symphony of groans for the next. This show has the kind of jokes where you’re kicking yourself because you didn’t see them coming. I love it. If I wrote you a list of all the songs in Les Mis and you had to guess the names of the parody version, I’m sure you would get a few of them right. We’d probably all get One Day More right. But here’s the trick...they’re still doing the songs. All the hits are there: I Dreamed a Dream, On My Own, Bring Him Home, you know, powerhouse songs. The words are different and they’re stuffed with gags, but this cast still hits all of those notes. It’s Fringe Season in Philadelphia! For the next three weekends the city will be drenched in culture and creativity. Performances take place all over the city and the best of them stretch the boundaries of what we think is possible in the theater. This guide is a list of shows that I’m excited about because they’re diving into the intersection between games and performance. Some of these pieces and their creators are very well known to me; others are complete mysteries. All of them catch some curiosity of mine around presenting theatre in new ways that create investment and agency for the audience.

Today’s post is something different. I have been writing fiction quite a bit recently, some for my D&D group, some just for myself. I’d like to share a short piece here as a little snapshot of my other creative work. I originally wrote this at the beginning of my current D&D campaign a couple years ago. This isn’t backstory exactly; it’s what happened the day before my character met the rest of the party. I present to you the first page in the tale of Rory, Gnomish Fighter: Bella wasn't actually listening. She'd heard what she needed; it was enough to know that he'd be paying for his room and all of his meals in advance. That kind of commitment wasn't often found, even in Vestrim's market district. Besides, who had ever heard of a broke gnome? In the post Introducing: Questo, I mentioned that I got my first taste of large-audience roleplaying at PAX Unplugged 2018. That was also my first full con experience. I got to game with some incredible heroes of mine and make some new friends. It was a pretty great weekend. So while the rest of the gaming world is in Indianapolis this week for that other con, I’m going to reminisce about PAX. There were two events on the schedule that I took up for research purposes. I knew I wanted to see how folks from the gaming sphere took on the challenges of performing. I was also grateful to have the opportunity to see the show from the audience’s side. The two events were:

Today I’m going to focus on To Serve Her Wintry Hunger because it most directly impacted my work on Questo and gave me a bunch of takeaways for bringing a game to a large audience. I saw a specific approach to running a full room through a small storygame, and I also experienced first hand what is fun for an audience in that setup. It was a cool event and made me an instant fan of Stephen Dewey.

This week’s topic comes courtesy of Sean DMR (@flying_grizzly and www.flyinggrizzly.net) who tagged me into an interesting thread on twitter looking at role-playing game frameworks through the lens of Lecoq territories. My graduate training at Pig Iron School was rooted in Lecoq, so I’m familiar with the territories through both an academic and a creative lens, but I hadn’t considered applying them to tabletop games. I’m delighted that Sean put this idea on my desk.

Alright, so what’s a territory? Simply put, the territories are different dramatic categories of theatre; the main ones we explore at Pig Iron are melodrama, commedia, bouffon, tragic chorus, and clown. As Sean points out, they are not the same as genre and you could make a commedia piece that is sci-fi just as easily as a western, for example. They’re also not the same as style. The territories may lead us towards specific style choices like slapstick or archetype, but the core identity of a territory comes from a dynamic drive that is amplified by the relationship between the characters and the world of the play. Beyond styles or genres, we seek to discover the motors of play which are at work in each territory, so that it might inspire creative work. And this creative work must always be of our time….......Our method is to approach the ‘territories of drama’ as if theatre were still to be invented.

I’m happy to report that our pilot episode of Questo was a success! We took our audience of about a dozen people on a fun little adventure game and received some very helpful feedback on their experience. I’d like to start with a quick thanks to the wonderful folks who came out; it was such a treat to present this new game for you and to see the inventive solutions you came up with during the story.

The audience wants more! Our players responded well to the item cards as props and took to the basic mechanic of turning one in with a description of how they would use it. I was surprised to learn that people have just as much fun hearing the solutions of the other teams as they do coming up with their own. The structure proved to be accessible for people and allowed them to learn the game as they played it. At the end of the evening, folks wanted to know when we’ll be doing the next one.

What did we learn?

Questo is a great machine for lateral, out-of-the-box thinking. Over the course of the game, players identify the goal to create the best story and learn that Jeff and I are rewarding big, risky, creative choices. At the same time, their toolkit is getting smaller, so they’re nudged to use things they wouldn’t reach for at first. We witnessed teams getting playfully inventive, not only in the way they used the items, but in expressing their characters and taking advantage of the opportunity to tell a story. By the end of the adventure, tables were combining their efforts, putting their heads and their inventories together to figure out the best way to get past the encounters. We got good feedback on the characters that we added to the world, and people enjoyed having them performed. This isn’t a surprise, but it’s a fun invitation to get deeper into the characters we're creating. I noticed the parts the players enjoy aren’t always what they find important. Several folks said that they enjoyed seeing us play characters in the world, but when given the opportunity to interact with them in the game, each team chose to do a clever stunt instead. Based on this one test, it seems players prioritize participating in the story we invite rather than taking control of the narrative. In encounters where we’d give a direct option or an alternative to change the scenario, teams chose the direct option most of the time. Even in the final moments, when we told them that the direct option would most certainly end in tragic death, the entire room decided to fall on the sword. They don’t mind that we’ve already written the story as long as they get to tell their version of it. What questions do we have? The main decision we need to make is how much Questo is a competition between the teams and how much is it a collaborative story game? In the feedback, we heard support for both. Some players wanted more clarity about the results of their decisions and who was ahead. Other players loved collaborating between tables and wanted more of that sooner. During the pilot, collaboration was working and driving the action in the room. Either we need to improve on the clarity of the competitive elements or we should cut it out altogether. An interesting lesson to observe is that the competitive part of the game, which was the most objective part for Jeff and I had the biggest sense of being arbitrary to the players. I’m also very curious to explore what it means to make the game a recurring, serial story. We have questions to answer around scaling the narrative and making sure the core game is fun to replay. I wonder whether it can support players returning with the same characters or having an opportunity to carry over something from the previous episode. What’s next? Honestly, the response from the pilot tells me that the piece is more ready than I expected. We have some work ahead of us to get it to its final form but I’m looking forward to running this again. This fall we’ll dive deeper into the performance and set up a run of a few games in a row to look at how it behaves over multiple episodes. If you’d like to find out when the next iteration is going to happen, there’s a google form at the end of this post. Following Matt Colville’s example, I will email you only once the next game of Questo is open. Off-topic tidbits

Kicking off Questo development we were excited about creating a role-playing game experience that had a different feel than other projects we had worked on. We were thinking about the reasons that folks don’t play RPGs, or don’t play them as often as they’d like and we came up with three:

We wanted to make a game where these obstacles were laughable. It needed to be simple and social, and flexible enough that players could come and go as they please. We began our process by making a “minimum viable product” (MVP). This is a Silicon Valley term that came into my lexicon from the Stop, Hack and Roll Podcast. The idea is that you make the simplest possible version of the game first so you can start testing and iterating as soon as possible. We gave ourselves one afternoon to make the MVP, which meant we would need to make a lot of quick decisions. The first major design question was what is the role of the audience, both as individuals and as teams. We opted to cast each team as a single character on an adventure with the characters from the other tables. During the Quizzo-style breaks, the team members will huddle up to discuss/debate/derail their choice as the character they’re all playing together. Once back in the adventure the characters will be working together to overcome different encounters. The game also needed a competitive angle to create tension between the tables and put some pressure on the decision making. The problem we were running into was how could we create dramatic risk for the characters without undermining the gameplay? If each character represented an entire table of people, we couldn’t risk having the characters get eliminated or separated without a plan for what we would do with that team for the rest of the game. We landed on a paradigm where the characters would succeed and advance between the encounters at the same time, but the question is how much does it cost them to do it, and who has the better story at the end? The last major question for the MVP was what would our role be as performers and gamerunners? How would we frame our interaction with the audience? Here, instead of taking a swing at the best answer, we’re going into the pilot with a couple different modes in mind that we’ll test in different encounters. Sometimes we’ll operate as neutral gamerunners, other times we’ll play characters. I’m most excited to test out the version where we play gamerunner-as-character, rooting on the characters and pitting the teams against each other. We’ll see which mode seems the most fun during the pilot. Another thing we’re testing in the pilot is how we can use the note cards that teams will turn in to capture their decisions. We realized we could have some fun by making them into kits of gear, to flesh out the characters and inspire the players’ creativity. At the beginning of the game, each table will receive a cache of items that their character has with them on the adventure ahead. The teams won’t know exactly what gear they’re selecting, they’ll simply have to choose one of the available monikers like “The One Who Rushes In” or “The One With the Keen Eyes” but for a little preview, I’d like to show you what one of the caches looks like. The team that picks the [redacted] moniker will get to take these fine items with them out into the wild world: If you’re in Philly and you’re interested in coming to the Questo pilot, shoot me a line and I’ll get you the details.

images from https://game-icons.net/ Questo is my current project in development with Jeffrey Evans. Jeff is a long-time collaborator who I worked with on Skills & Scars in last years Philadelphia Fringe Festival as well as the Science After Hours events at the Franklin Institute. Questo is our latest exploration bringing gaming into our performance work, and our goal is to create a game that an entire audience can play together in a casual setting like a pub or cafe. Eventually we’d like this to be a recurring event with a serialized narrative. We’re running a pilot episode at the end of this month as our first playtest to see how an audience responds to it.

The concept for Questo originally came during one of our green hat brainstorming sessions for Skills & Scars. When thinking about all the different ways we could implement or tinker with a role-playing game for a live audience we wondered what it looks like to have a large audience all playing the game with us. It was a natural response to the work that we were making at the time. Skills & Scars was small and intimate; it was a piece about feeling comfortable and welcome and taken care of in a friendly atmosphere. Questo came out of the question of “what if we did the opposite?” What if instead of being small, safe, and comfortable it was big, public, and raucous. Would that be a good time? We wondered about a hybrid between Quizzo and a tabletop game. I had a few different experiences of large audience role-playing at PAX Unplugged last year which I’ll dive into in a future post, but one of the immediate takeaways from seeing other people’s attempts was that a lot of work should go into delivering the game to the audience and providing clear structures for their involvement. When game designers talk about role-playing games at their most basic level, they often describe them as a conversation. In Blades in the Dark, John Harper uses this breakdown: The GM* presents the fictional situation in which the player characters find themselves. The players determine the actions of their characters in response to the situation. The GM and the players together judge how the game systems are engaged. The outcomes of the mechanics then change the situation, leading into a new phase of the conversation—new situations, new actions, new judgments, new rolls—creating an ongoing fiction and building “the story” of the game, organically, from a series of discrete moments. *GM stands for Game Master, the player who is running the game for the other player characters Zooming in on those first two sentences, there are two key channels of communication that need to be established: describing the fictional scenario and determining the character’s actions. At a table with a handful of players, this is simple to manage conversationally, but with a whole room of players it begins to get unwieldy. At the structural level, this made me think of Quizzo as a possible framework. In Quizzo, the two channels are very distinct. The hosts use a microphone to give the audience the rules and prompts for the game and the teams turn in index cards to capture their input. Could we use this format to run a roleplaying game? Structurally it makes sense, but there’s also a question of rhythm. Tabletop gaming thrives on impulse. During a game, we expect the gamerunner to put us under pressure to make quick decisions. This creates immersion and stakes. Your character doesn’t have time to find the perfect choice so just leap into the action! This is also for dramatic pacing and tension. A skilled player is going to make their decision quickly so that everyone else stays engaged and the game can keep moving. Contrast this with Quizzo where the breaks between questions do have a certain time limit, but that limit is intentionally long enough to allow people to order another drink, chat with their friends, second guess their responses one too many times, etc. If we bring that rhythm to tabletop, how does that change the experience? If people don’t need to be on their toes thinking and responding, are there other things that can arrive? These are some of the questions and curiosities that we had at the launch of our Questo development. Next time I’ll talk a bit about our process and implementation and preview some of the things we’re building for the pilot episode. Hi, I’m Devin again. I’m going to talk a bit about what I’m up to here

I’m making my own space to explore theatre and games. I’m a theatre maker who’s interested in building games and bringing ideas from gaming into my performance. This blog is a place to explore some of the big questions and ideas that arise when combining these two forms. There is an excellent community of thoughtful makers in the gaming community, especially around tabletop roleplaying games, and I want to bring my own perspective of theatricality and playful performance to the conversation. Beyond that, I’m making a public record of my work. I have found myself walking the life of an artist, and I am still trying to figure out what that looks like. Most of my recent work has been engaged in combining these two languages; melding theatre and live performance with games and game design. I began creating a few projects and calling them “experiments” but here’s a little secret: I hate calling art experiments! Look, I went to college; I have a science degree. I know what experiments are, okay, they have hypotheses. Right? They have methods. They have evidence. They have results. They have reports. If you’re going to call your project an “experiment” than you’d better have the records to prove it. So far, for my work, the records aren’t great, and I’d like to change that here by writing a bit about what I’m curious about and what I’m pursuing. Hopefully there will be some results to share, but all in good time. An excellent teacher of mine once gave me the very simple-seeming advice of “notice what you notice”. In doing that I’ll mostly look at tabletop games and live theatre, but there might be interesting things to notice from video games or video theatre too. When I look at the way people design and engage with role-playing games, I’m excited by the way they create shared narratives, authorship, and consequence. I think these things are rad, and they belong in the theater. People are incredibly passionate about the stories they create in games, partly because games allow people to test their ideas about story and discover what moves them. What can the theater’s magic add to games? What happens when we playtest our performances, when we ask what makes them fun? I come to these forms as a player first. The lights of the stage and the seat at the table are completely different animals but I want to work with both of them. They create different states, have different rules and I’m curious about that. Is being in front of an audience when the curtain comes up actually different than when it’s your turn in initiative order? Should it be? I’m not sure, but those are the type of questions I’ll be investigating. Oh! I should definitely clarify something about the type of theatre that I make. I’m a clown. I mean I’m also an actor, but clown and physical theatre are my loves. I make work that is devised, which for my money mostly means that it’s adaptable. So I make work that is adaptable, that uses the body, and usually tries to make you laugh at something. As an artist, I’m interested in joy, hope and reason. More on that later, we’ll have plenty of time to meet each other. I just didn’t want you walking away from here thinking I was one of those actors whose not a clown. Because I’m definitely not. |

Archives

January 2021

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed